Michael Shermer

One of the most frequent criticisms I receive is that I’m accused of being arrogant, a charge I will not deny. When one becomes extremely confident in the logic of his or her argument, it often comes across as arrogance. And to be brutally honest, I’ve gotten bored with responding to the average atheist’s arguments against God, because they usually aren’t very good and don’t require a great deal of effort to refute. To those aspiring to become evangelists of atheism (after all, Dr. Richard Carrier offers online courses in “counter apologetics” for atheists) my best advice would be to learn how to think critically — merely parroting Richard Dawkins, Richard Carrier or Sam Harris won’t win the competition for ideas against the likes of John Lennox or William Lane Craig. Or my own arrogant self, for that matter.

Quite frankly, the gladiator-style duels with amateur atheists that pass for debate on the internet have become old hat and really don’t present much of a challenge for me anymore. They are extremely tedious and very predictable. And after making the same basic argument for the existence of God about a decade now, I’ve yet to encounter a better argument coming from an atheist trolling the internet.

On the other hand, a debate against a serious, well known and well respected nontheist like Michael Shermer could prove to be very interesting and worth the effort for me. Of course, the first challenge will be to engage Mr. Shermer in dialogue, unless I look for an argument to destroy that he’s made in the past. He’s got plenty of material available on the internet.

When former president of American Atheists Ed Buckner and I met to debate, he also came prepared with a methodical argument for atheism that he’d polished over the years. The problem for Ed was that I had anticipated every argument he might possibly make in our debate beforehand, because he apparently follows the same script every time. Slated to begin the debate (because Ed wanted the final word), I enumerated the same seven bullet points that Ed would cover in his spiel in my opening remarks, and proceeded to eviscerate them before he ever got a chance to speak. That debate was fun to preparation and a great experience, but the most disappointing aspect of it was that we barely scratched the surface of my argument for God. We were both so focused on our battle of wits over Ed’s argument for atheism that we ran out of time to even mention my best scientific arguments for theism, my Big Picture argument.

Back to Michael Shermer, in one of the atheist-versus-theist “discussion” groups on Facebook (debate is obviously the wrong word to describe the immature trading of insults, standard fare for this sort of social media platform) someone posted an article by Derek Beres from Big Think titled “Understanding (and Refuting) the Arguments for God,” which claims to present ten arguments for God and the rebuttal arguments by Michael Shermer, from his book How We Believe: The Search for God in the age of Science. To avoid rather than exploit the same disadvantage I had over Ed Buckner, where I knew his argument but he didn’t know mine, I would be more than happy to provide Mr. Shermer (and Mr. Beres) with a free digital copy of my book Counterargument for God, so that they might fully understand the actual arguments that would need to be refuted, and not those straw man arguments suggested by Beres’s article.

To avoid rather than exploit the same disadvantage I had over Ed Buckner, where I knew his argument but he didn’t know mine, I would be more than happy to provide Mr. Shermer (and Mr. Beres) with a free digital copy of my book Counterargument for God, so that they might fully understand the actual arguments that would need to be refuted, and not those straw man arguments suggested by Beres’s article.

At this point, I have less interest in “winning” another debate as much as seeing if any argument for atheism can actually demonstrate superior logic and reason that is supported by scientific evidence.

Assuming that Mr. Beres has accurately conveyed the work of Mr. Shermer, the title of his article immediately becomes problematic as it becomes painfully obvious from the very first bullet item that Mr. Shermer actually does http://antihousewife.com/category/whole-30/ not understand the arguments for God, so it would be virtually impossible for him to successfully rebut them.

For example, the first two arguments that Mr. Shermer proposes to refute are the Prime Mover and First Cause arguments, which Mr. Beres curiously asserts “rephrased, (means) God either must be in the universe or is the universe.”

With all due respect, that isn’t what the First Cause argument says at all. The First Cause argument simply says that Lębork everything that comes into existence must have had a cause.

Furthermore, theists more commonly will offer the Kalam cosmological argument, which uses the principle of First Cause as follows:

- Whatever begins to exist has a cause.

- The universe began to exist (The Big Bang event.)

- The universe has a cause.

By this point Mr. Shermer’s rebuttal argument to the First Cause argument has already failed miserably and completely, because he never correctly understood the argument he proposed to defeat.

The supernatural Creator of this universe would neither exist within this universe, nor be the sum of everything in the universe (which is pantheism.)

This seems to correspond with the old atheist’s canard that God is nothing but “an invisible man in the sky” when in fact God is not human nor even part of this universe.

God is not merely an extra terrestrial; by definition created through an understanding of physics, God would be extra universal.

There are also problems with the very first sentence of the next argument, which Beres/Shermer refer to as the Possibility and Necessity Argument, which was asserted to be: “Not everything is possible, because that admits the possibility there could be nothing. If nothing had once existed, the universe could not have come into existence.”

The problem with that bit of pretzel logic is physicists have made exactly the opposite claim — this universe is believed to have had an origin, commonly called the Big Bang. And prior to the Big Bang, nothing existed — not even a single atom.

There simply is no evidence that a multiverse or quantum foam exists.

One of the atheist’s favorite arguments against God, that lack of evidence is also evidence of absence, can be applied here equally well to the atheist’s arguments that something always had to exist — it is an assumption.

While it might seem logically impossible for an entire universe to be created from absolutely nothing, nevertheless that certainly appears to be the opinion shared by most experts in physics and cosmology on the origin of the universe. We know this universe exists. We also know it hasn’t always existed.

But that’s about all we know for sure.

Looking over the rest of the ten so-called arguments for God listed by Michael Shermer, some were arguments I would never offer in a formal debate, such as Pascal’s Wager or fideism. Faith is certainly important, but it isn’t an important part of my argument for God.

Shermer defines the moral argument as this question: “How can there be morals without God?” and then says that it would be ludicrous to assume everyone would turn into murderers, rapists, and robbers if God did not exist.

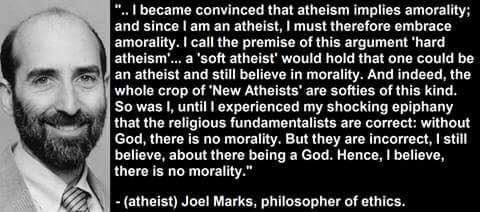

But again, that isn’t really the moral argument for God, at least not the one I would make: “Is morality objective, or relative?” is the better question, in my opinion. If morality is objective, it can only come from God. If morality is relative, it will differ from person to person.

Besides, not all atheists even agree about the existence of morality.

Besides, not all atheists even agree about the existence of morality.

If God exists, adultery is morally wrong. Always. Period. No exceptions. If God exists, abortions would be immoral because having sex outside of marriage is immoral. Rape, robbery, and murder are criminal offenses, both illegal and immoral. Behavior as such is objectively understood to be morally wrong, which is why it was codified into law as punishable criminal activity.

To successfully refute an argument, one must first understand it. Either Shermer or Beres or both of them have misrepresented the moral argument. In fact, they don’t seem to have gotten any of the arguments for God right.

Not to mention, there are much better arguments for the existence of God than the moral argument.

What Shermer calls the “mystical experience” argument, which is about mystical or spiritual experiences that Beres dismisses because they can artificially be caused by ingesting LSD or some other hallucinogen. It should come as no surprise that hallucinogenic drugs can cause hallucinations, though. And there are several problems with the Shermer/Beres description of the argument as well as their rebuttal.

The first problem with atheists claiming that miracles don’t occur is that several other prominent atheists have described personally witnessing, investigating or experiencing miracles themselves. It would be presumptuous and unkind of me to assume Dan Barker or Jerry DeWitt were lying about their past experiences. The other significant problem with the atheist’s rebuttal to the miracle argument is a type of scientific evidence called corroborated veridical NDE information. This evidence describes accurate new information learned by the human mind independently of a functioning brain tissue, communicated after physical recovery, and then investigated and verified by independent researchers to be true.

Mr. Beres also wrote that he saw no reason to attribute chemistry to a creator, but that only tells me that he’s never listened to a lecture by Dr. James Tour speaking on the subject of abiogenesis. Life cannot evolve until it exists.

Shermer’s most pitiful effort was his “anti” teleological argument, the argument for intelligent design. Quite predictably, he cited perceived design flaws in living organisms and referred to purported “vestigial organs” such as the alleged hind legs in pythons.

The biggest problem with this particular argument against intelligent design is the simple fact the critics themselves can’t produce the superior design.

Atheists posing as neuroscientists will quickly tell anyone who will listen that the human eye is poorly designed. However, where is the artificial eye produced by humans with superior function and capabilities? If the organic eye created by nature really is so terrible, why don’t we manufacture our superior artificial eyes that are intelligently designed by humans?

Because we can’t…which reminds me of an old cliche I learned in my very first year as a professional software developer: those who can, do. Others criticize.

All that said, the real argument for intelligent design is a very logical and all encompassing one that I like to call “The Big Picture.”

The Big Picture argument for intelligent design primarily focuses on all the statistical probabilities related to analyzing and attempting to answer existential questions. It begins with improbability associated with a fine-tuned Big Bang anomaly, and what we know about inflation of the early universe based on the work of physicists such as Martin Rees, Roger Penrose, and Stephen Hawking. The Big Picture also includes what we’ve learned from chemists such as Ilya Prigogine and James Tour about the improbability of an accidental, unplanned origin of life event known as abiogenesis.

In short, Mr. Shermer barely scratched the surface of my argument for design, which for the record does not lack scientific evidence. Complimentary systems and food chains are but a very small part of that argument. The very same scientific evidence alleged to show proof for the theory of evolution — meaning DNA analysis, comparative anatomy and the fossil record are used in the design hypothesis I’ve dubbed “iterative creation.”

Once statistics are introduced into the design argument and applied to every facet of science involved to answer the existential questions, it becomes painfully obvious that by all logic and reason, we should not exist.

This fine-tuned universe should not exist. This universe is so highly improbable that the only way it can be deemed possible is if an infinite number of alternate universes that were not fine-tuned were also created at the same time by random chance, but failed to develop. This is known as the multiverse hypothesis. The only reason we’re having this discussion, though, is because this universe does indeed exist. Before the Big Bang advanced from hypothesis to become theory, it was common for people to assume the universe had always existed, because a universe with an origin creates some very serious logical problems. A universe with an origin can only have two options: it came into existence as the result of an extraordinarily serendipitous, perfectly timed sequence of events, or the universe was created by an astounding form of intelligence, for a specific reason (although we may not recognize or understand the logic behind that reason within the confines of our own mortality.)

There is no third alternative. We’re either here by accident, or we exist on purpose.

It seems that both sides suffer from insufferable arrogance. Atheists have the arrogance to presume that what we know is almost entirely correct but for the details, but worse assume that we know the limits of what we do not know. Theists have the arrogance to assume that key elements of what we know is incorrect or misinterpreted, and worse assume that we are limited in what we can know.

Both are, of course, wrong, and from a scientific standpoint only agnosticism is a valid worldview until and unless G-D shows up and participates in a double blind study (I keep asking but the jerk won’t sign the IRB forms 🙂 ). Certainly science has constrained the possible characteristics of any deities (including those believed by the vast majority of theists), but not eliminated them.

PS – as we’ve sort of discussed, although it on the surface has great appeal, the “fine tuned Universe” argument just doesn’t work for physical and mathematical reasons, and to an extent is an offshoot of the increasingly discredited string theories (and mutiverse hypotheses, which aren’t even real scientific theories). It’s sort of like saying “aha – 2+1 = 3 therefore design!”; no, it doesn’t, it’s an intrinsic interactive property of system. I wish theists would drop it.

Two things you said, Chuck, that cause me to think (for which I am always grateful):

You said there are no limits on what we can know as human beings, but I believe there are. We cannot claim to “know” what will happen when we die; we can merely claim what we believe will happen. No matter how many thousands of NDE accounts I read, the evidence culled from them can buttress my beliefs, but it cannot turn those beliefs into knowledge claims.

The second thing you said that caught my attention was that “something” (the fine-tuned universe argument, perhaps?, or the illusion of design?) was an intrinsic property of system — to which I would counter that systems collect input data which is processed into information as output.

Which is absolutely a function of intelligent behavior, so I don’t understand your point. I don’t understand an argument where complexity and organization occur by random chance.

The fine-tuning argument, applied in limited form only to the Big Bang itself, asks a simple question in respond to your 2+1=3 argument — could the values have been different?

Remember, I can’t even argue whether Rees correctly identified the “right” six cosmological factors he came up with in his analysis of fine tuning, or that he assigned the correct values to them. I must rely on other physicists reviewing his work and saying basically, he’s not stupid. The very fact that Rees claims that these six cosmological factors exist becomes an exercise in faith for me, to assume he knows what he’s saying, and that those who agree with him also know what they’re doing. Compared to the experts, I know nothing about physics or cosmology.

The real question is whether or not these cosmological values should be treated as constants, meaning they couldn’t possibly have any other value, or variables, which multiverse hypotheses imply. And then once we’ve had this “discussion” we can talk about all of the other systems that come after the Big Bang which also appear to have been “fine-tuned” so that we and every other living organism on earth would exist.

Thanks for the great comment!

To be clear, I didn’t say there were no limits on what we can know. I said theists … “assume that we are limited in what we can know. ” I am trying to say it is dangerous a priori to assert we “can’t know” something, and to hang your belief system on that assertion. Big difference. NDE’s and neurology aren’t my fields, but you state affirmatively that we cannot know what will happen when we die. We don’t know what kinds of neurological tools will be available in 10 years, much less 100. If we reach the point where we can map and model the human brain at the molecular level (not currently possible, but theoretically not at all out of the question), can predict detailed human behavior with those models (thus essentially disproving free will), and reproduce NDE’s, then yes, we would be able to say with reasonable certainty that we know what will happen. That is what the atheists of the “no free will” camp (eg Jerry Coyne) would assert. But you can’t make that assertion until you actually do the experiments. So NDE’s would be an example of “something we don’t know but might some day know” rather than “something we will never know”.

Here’s an example of the same error from the other side of the house, that leads in to your second “thingee”. Those who propose the multiverse hypothesis (please don’t dignify it with the term theory) say that you can’t detect the other universes. First of all, that makes the multiverse hypothesis by definition untestable, and therefore not real science and definitely not a “theory”. A few physicists are even arguing that mathematics is “above the scientific method” and believable without the ability to test it experimentally – they are just as full of crap as those who argued for the Ptolemaic System of planetary motion because it was mathematically beautiful (and which was later proved wrong). Second, while the technical hurdles are currently unknown, it also assumes a limit to our knowledge on a subject for which there is zero evidence we have a limit.

This gets into a very complex subject not easily addressed in short blog posts/responses, but in integer math, given two fixed values, you only get one fixed result when they are added. That is an intrinsic feature of integer math. While immensely more complex, some physicists posit that the various “constants” we see are interrelated in ways we do not presently understand, or understand only tentatively. I’m simplifying a lot, but take the electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces. Originally these were thought to be separate, but under the standard theory, these are actually just different manifestations of what is called the electroweak force. The Z and W Boson masses were predicted, and later found, and the current Higgs Boson work also seems to confirm this. Again, simplifying, the bottom line is that those six “constants” Rees talks about might well be variables resulting from a smaller subset of constants – which would quickly increase the probability of a universe that looks like this one, perhaps even to 1.0.

One thing you did touch indirectly which is important from an apologetic standpoint is that the traditional Christian worldview is panentheistic. Thus, for a true Christian (much like that mythical true Scotsman 🙂 ), all this argument over science and this or that theory is actually irrelevant. This is why I think it’s fools game for apologists to try to argue for God on scientific grounds. The science can and will change. The current limits of our knowledge are temporary, and change in unexpected ways. Traditional Christianity offers a timeless faith that is outside and above the world; it’s only with the post-Augustine worldview and Protestantism that Christians tried to engage the Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution on worldly terms, rather than on God’s terms – an engagement it is bound to loose.

BTW, do enjoy your posts – and share your frustration the discussions on this topic are not more substantive.

I love reading your comments, Chuck. My brain gets a serious workout, every time. I really appreciate that, and hope you never stop reading my work and offering your insights.

Now on to point — when I offer corroborated veridical NDE information as “scientific evidence” that supports my theistic/spiritualistic-oriented worldview, my atheist friends will frequently fixate on the “NDE” aspect and belabor the point that we cannot “know” what happens when we die and “near death” is not actual death, and it soon becomes clear that the important aspect of the alleged phenomena, which is accurate new information obtained by a demonstration of quantum consciousness, is not something they care to discuss.

The other problem with my avoiding science is that atheists with reputations as prominent scientists misuse their position of authority to present a purely atheistic, naturalistic worldview that ignores a significant component of reality and the world around us.

It seems that theists and atheists are equally suffering from the Bill Clinton-esque problem: what is the definition of ‘is?’ In this context, what constitutes scientific evidence, and what does not?

This subject is eating up way too much of my time this morning – got serious work to do!

Just a quick reply that I’m not suggesting avoiding science, but I don’t see getting into the weeds of this or that theory as very productive, especially when you get to the fringes of modern science. Not only is it dangerous (new data can disprove your theory and damage the credibility of Christianity), it just isn’t necessary from a traditional Christian theological perspective. As for your specifics, certainly there are macroscopic manifestation of quantum effects, but “quantum consciousness” is just an untested hypothesis AFAIK. Which raises an issue we’ve discussed before, and one many scientists get annoyed over. A true scientist (like our true Scotsman) won’t jump between fields they aren’t conversant in. That doesn’t mean I think you are right on NDE, or am awed by your arguments, it just means I don’t have the background to discuss them. Modern science is pretty specialized. I can discuss quantum mechanics as it applies to tunnel diodes, geophysics, or stellar nucleosynthesis, but not neuroscience.

That said, you are absolutely correct that some scientists who are atheists convolve atheism and science, implying the latter definitively supports the former, and should be called out on that. And it is there that I would suggest that the apologist concentrate their efforts. Example: the multiverse theory and those who promote it as supporting an atheistic worldview should be *savagely* attacked as pseudoscience, using the language and standards of science. But proposing the “tuned universe” theory (which often uses the language and terms of the multiverse theory), isn’t doing apologetics any favors because it is equally vulnerable.

It’s nice that the scientific method is so successful, and so respected, that both sides of this debate want to cloak themselves in its respectability, but this debate is damaging the reputation of the scientific process (although not to the degree that the climate debate has – but don’t get me started on that!) – something I mostly blame the gnu atheists for.